Traces of copper around remains from Marie de Bretagne

When exceptionally preserved, hair, wools, or skin samples can have a high archaeological value. The best-preserved specimens have often benefited from specific environmental conditions that slowed down the degradation of tissues: intense dryness, coldness or absence of oxygen. A French team had a deeper look into the remains found in Marie de Bretagne’s sepulture (15th c., France), which did not benefit from such a specific environment. Using microscopic analysis under synchrotron radiation (SOLEIL and the ESRF), scientists showed that extraordinarily well-preserved hair samples contained traces of copper and lead that could explain this remarkable state. They also identified the unexpected origin of the metal remains.

In 1477, Marie de Bretagne, Abbess of the Fontevraud order, died and was buried at Prieuré de La Madeleine in Orleans. The burial site was most probably desecrated during the French Wars of Religion that were raging in the 16th century. However, her coffin was partly found in place, along with human remains that included bones, teeth and hair locks. Among the latter, some were in an exceptional state of preservation and several centimeters long. It is a surprising discovery, in a temperate burial context where the degradation of such fibers could have been total. A team from IPANEMA (CNRS, French Ministry of Culture), the SOLEIL synchrotron, LPS Orsay, INRAP and the PACEA laboratory in Bordeaux, decided to unravel the mystery of the processes that led to the preservation of the hair locks (taphonomy).

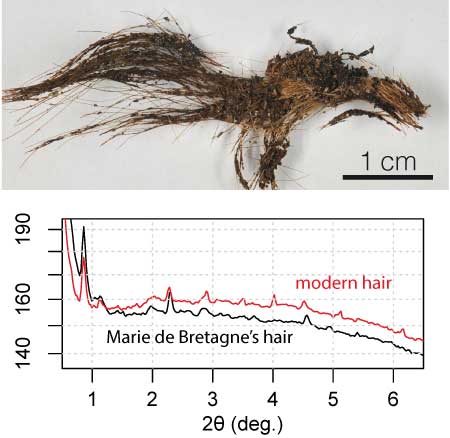

They first had a closer look at the actual state of conservation of the samples. The structure of the keratins inside the hair cortex is very well preserved (cf picture), from the macroscopic to the atomic length scale. Among the methods used by the scientists, some are based on synchrotron radiation (at the DIFFABS beamline of SOLEIL and the ESRF). Microscopic data demonstrated the preservation of the fibrillar structure of hair keratins, as well as the presence of many chemical elements deposited in the sample, in particular calcium, lead and copper. The concentration of some of these elements was 1000 times greater than what is typically found in recent hairs.

Researchers then wonder: if the hair strands were found in such a good state, something must have inhibited keratin degradation mechanisms. The origin of calcium and lead seems obvious: calcium is abundant in environmental waters, and must have been incorporated during the life of the Abbess or post mortem. Lead is the main material of the coffin.

However the mystery of the origin of copper remains.

From the high concentration found, the most likely hypothesis is that Marie de Bretagne would have been buried with several copper-based artifacts. They would have quickly degraded leading to impregnation of the remains with copper. Diffusion of copper in hair fibers may have stopped the protein degradation mechanisms, leading to their rediscovery 5 centuries later.

These results led to a reexamination of the remains from the Orleans coffin. The scenario proposed was confirmed by the discovery of millimeter-sized fragments of copper-based artifacts, among which a rivet and the possible remains of a pin placed with Marie de Bretagne’s body.

The high-resolution analysis performed with synchrotron radiation will thus have allowed the indirect detection of the presence of metal artifacts present in the burial in the first place, thus completing our lacunar knowledge of the events, half a millennium after they took place.