Contribution of the HERMES beamline to the study of "Tubenets”: Network-like structures built by bacteria inside insect cells to feed more efficiently

The cereal weevil, one of the world’s main crop pests, harbors symbiotic bacteria that live inside its cells. Scientists from INRAE and INSA Lyon, in collaboration with experts from the SOLEIL Synchrotron and Claude Bernard University in France, as well as the Max Planck Institute and EMBL in Germany, have discovered that these bacteria build complex, network-shaped membrane structures. These structures increase their surface area for exchange with the host cell, allowing the bacteria to absorb an essential nutrient: sugar.

This is the first time that bacterial structures of this scale have been observed. The SOLEIL’s HERMES beamline contributed to this discovery.

The cereal weevil is one of the major pests affecting cereals such as wheat, rice, and maize, both in the field and in storage. It feeds directly on the grains, but it is not alone: it hosts symbiotic bacteria that live inside its cells. These bacteria, named Sodalis pierantonius, reside in large numbers within specialized insect cells. They provide the weevil with essential nutrients that are absent from its cereal-based diet. This is a mutually beneficial relationship: the bacteria use the sugars produced during the digestion of grains and, in return, supply the insect with essential nutrients such as vitamins and certain amino acids.

While scientists have long understood the importance of this exchange, its exact mechanisms remained unknown. To investigate, the researchers used electron microscopy with an advanced sample preparation method that preserves membranes more effectively. For the first time, the team observed original tubular patterns forming complex membrane structures built by the bacteria. To study the architecture and composition of these structures, the scientists developed new 3D microscopy and analytical methods using the SOLEIL Synchrotron particle accelerator.

Bacteria build an exchange network called “Tubenet”

Analyses reveal that these structures form a complex network of tubes, 0.02 micrometres in diameter and several micrometres long, which connect bacteria to one another through numerous interconnections.

At SOLEIL, scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) was used on the HERMES beamline to identify in situ the nature of the carbon content within these tubes and in host vesicles located close to the tubes, and to determine whether the tubes serve as nutritional interfaces between the insect cells and the symbiotic bacteria.

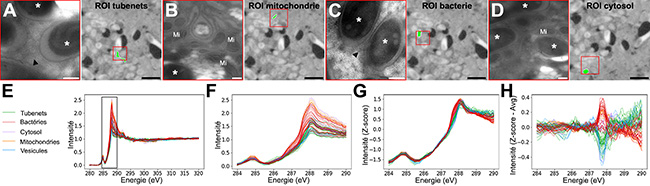

On thin sections (70 nm) of the bacteriome, the host tissue that harbours the bacteria, series of images were collected over areas smaller than 10 µm² with 50 nm steps and at each energy increment across the X-ray energy range corresponding to the carbon K-edge. The carbon signature (XANES spectrum) was then analysed in 85 selected regions of interest corresponding to the tubes, bacteria, as well as the cytosols, mitochondria and vesicles of the insect host (Figure 1).

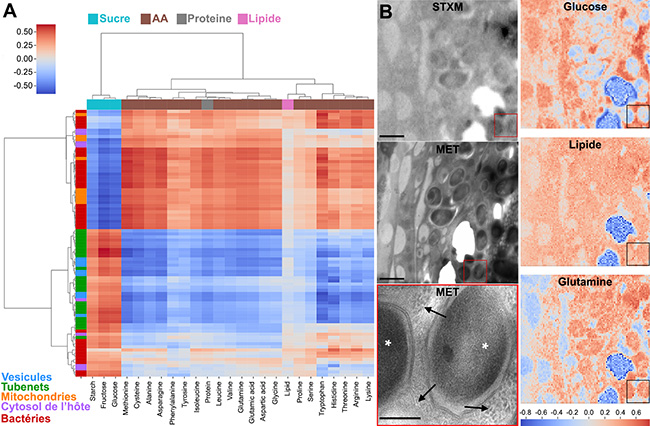

Processing of the spectra using a clustering approach (Figure 2), or a more traditional approach consisting of modelling the experimental spectra using reference spectra, revealed a higher abundance of carbohydrates in the tubes and host vesicles than in the insect mitochondria and the bacteria. The similarity in composition and the enrichment in carbohydrates in both the tubes and the host vesicles indicate a pathway for carbohydrate transfer through these membranous transport structures, on both the host and bacterial sides.

Thus, just as the structure of intestinal microvilli1 in humans increases the exchange surface to improve nutrient absorption during digestion, these tubular structures allow bacteria to increase their exchange surface with the host cell in order to better assimilate sugars. In return, the bacteria produce essential nutrients for their host. The research team named these structures “Tubenets”, a contraction of tube and network, in reference to their shape.

While structures that increase exchange surfaces to enhance nutrient uptake are well known in multicellular organisms (intestine, plant roots), this is the first time that such a structure has been demonstrated in bacteria. Similar structures may exist in other types of bacteria.

The results, published in Cell, open new research avenues for understanding microorganisms —particularly those living inside host cells— and offer promising new directions for combating crop-damaging insects.

1 – Microvilli: Tiny, finger-like projections covering the cells of certain tissues such as those in the gallbladder or small intestine. They facilitate the absorption of external substances like nutrients.