"Moon milk": Next Chapter

"Moon milk" is a strange substance that covers the walls of some prehistoric caves, sometimes erasing parietal works. What is it made of ?

A research was carried out on the infrared beamline SMIS in 2009. As part of our series 'Next Chapter', we reconnected with the scientists filmed in 2009 and asked them how their research has progressed since then.

In 2009, paleoclimatologist Dominique Genty arrived at the SOLEIL synchrotron with Petri dishes containing a strange white substance reminiscent of Camembert rind. However, this soft, milky material was collected from the walls of a prehistoric cave. It is known as "moon milk," or more commonly "mondmilch." In Lascaux, several thousand years ago, it covered an entire corridor and likely concealed paintings that are now inaccessible. At Chauvet, more than 30,000 years ago, prehistoric humans drew animals with their fingers in the mondmilch on the cave walls, and these perfectly preserved drawings still appear fresh and striking.

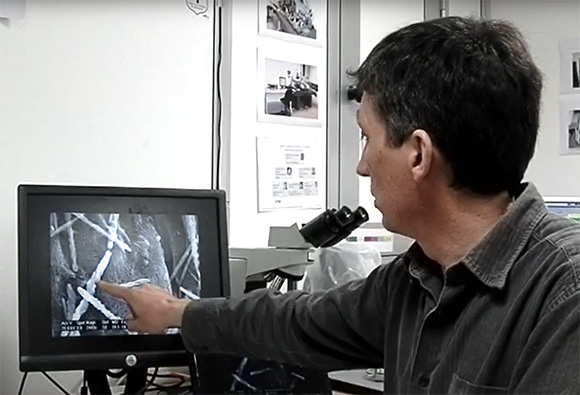

According to electron microscopy images, mondmilch seems to be a mixture of calcite and organic matter. At SOLEIL, Dominique Genty chose to analyze his samples using the infrared radiation from the SMIS beamline. The measurements revealed characteristic signatures: those of filamentous bacteria and fungi. Mondmilch is, therefore, a complex assemblage of water, mineral matter, and living organisms—now fossilized. "It's astonishing to see how lively this material, which is tens of thousands of years old, still appears," comments the paleoclimatologist.

These findings supported the thesis defended by Florian Berrouet in December 2009, under the supervision of Jean-Michel Geneste, the curator of the Lascaux cave. He documented an impressive number of caves covered in the whitish substance and regarded mondmilch as a true imprint of archaeological time, as well as a medium in its own right for parietal art. It's as if today's artists were to say they commonly work with charcoal, watercolor... and mondmilch.

Meanwhile, Dominique Genty broadened the scope to include calcite formations known as rimstones or "gours," deposits found in caves that form small dams retaining water. He embarked on an extensive dating campaign of these rimstones using carbon-14 and uranium-thorium methods. The rimstones, structurally related to mondmilch, date back 8,000 years. "With this study, we even made the cover of the journal Radiocarbon," Genty recalls with great pleasure.

Today, he leads a major project supported by the ANR, named DECACLIM, which aims to understand how climate change affects decorated caves. The project also seeks to define appropriate conservation methods. Dominique Genty has access to some of the longest data sets in the world, spanning nearly thirty years. It was in the 1990s that he had an inspired idea: to equip numerous caves with sensors measuring temperature, humidity, and CO2. His data reveals a clear trend, such as an increase of about +1°C in temperature. The project will last four years and will include, among other things, the modeling of air flow and its condensation on the walls within a decorated cave.