Through a series of portraits, SOLEIL goes out to meet the people who make the synchrotron what it is. For this fourth episode, Stéphanie Belin, a scientist on the ROCK beamline, played along. From LURE, the forerunner of SOLEIL, to its upcoming upgrade, she has been part of the major milestones in the synchrotron’s history — including the construction of two beamlines, SAMBA and then ROCK.

An adventure that has been as human as it has scientific, filled with a daily routine rich in encounters and diverse projects.

Although Stéphanie Belin, scientist on the ROCK beamline at SOLEIL, initially dreamed of space exploration, it’s ultimately the world of new materials that satisfies her thirst for discovery: “Studying the inner workings of materials to better understand their properties is the driving force that led me to scientific research,” she explains.

From industry to research

After spending the first 25 years of her life in Brittany, between Côtes d’Armor and Ille-et-Vilaine, Stéphanie Belin completed her final-year master’s internship in 1994 in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées, at an SME that manufactured ceramics and composites.

“I discovered the unique world of small private companies, where in-house laboratories competed against each other,” she recalls. “Research became too financially burdensome, and the engineers in charge of the labs were fighting for their team’s survival.” While the staff proved to be “incredibly kind” to her, she couldn’t see herself working long-term in “such high-pressure conditions, which stifle creativity.” A mixed experience, but one that would prove decisive:

“I called my Magistère supervisor to say that if there was a way to continue with a PhD through a grant from the Ministry of Education, I was in!”

In July 1994, “overjoyed,” she was offered a PhD position at the Solid State and Molecular Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory on the Rennes 1 University campus. Stéphanie then continued with a postdoc in Bordeaux at the Institute of Condensed Matter Chemistry (ICMCB), researching a new rare-earth-based luminescent material to improve red color in plasma screens.

She later took on a temporary teaching and research position (ATER) at the Institute of Nuclear Physics (IPN) at the University of Orsay (now Université Paris-Saclay), moving to the Île-de-France region. A friend introduced her to the Laboratory for the Use of Electromagnetic Radiation (LURE), a synchrotron facility scheduled to close in 2003, with SOLEIL set to take over.

Drawn to the unknown

“I chose to work at a synchrotron out of curiosity, since I had never used a large-scale scientific instrument,” she says. “I was intrigued by another PhD student in my thesis lab who did experiments at LURE: I was finally going to see what it was all about!”

Plus, “a new facility — SOLEIL — was on the horizon, with brand-new beamlines to be built. Everything had to be done from scratch.”

While others might have been daunted by the scale of the challenge, Stéphanie found it exhilarating.

“So, I joined the synchrotron world in September 1999” to work on a beamline project for the future SOLEIL synchrotron. She vividly remembers her first day: “It was marked by a staff assembly because the SOLEIL [1] project was at risk of losing funding from the Ministry of Research,” she recalls. “There was a real fervor and an unyielding determination in the room to do whatever it took to save the project and change the government's mind.”

She became part of the fight to bring SOLEIL to life. “I was immediately welcomed by everyone, regardless of role or background. Then I was mentored by a team of physicists and chemists who shared their skills and passion for the project. I felt incredibly lucky to become part of the big ‘Lurons’ family.”

Scientific research and supporting users

Today, Stéphanie Belin’s daily work has two main aspects: her research on electrochemical energy storage and supporting users on the ROCK beamline.

“My field involves electrode materials. I use my X-ray absorption spectroscopy expertise to assist research teams from other French and international labs,” she explains.

With this high-energy X-ray technique, researchers can study functioning electrodes in simplified batteries. This enables them to understand key phenomena like self-discharge, capacity loss, or low operational voltage — and seek improved material solutions.

“We’re free to choose our research topics, as long as they align with the capabilities of our beamline,” Stéphanie notes. “We build relationships with scientists and provide expertise to characterize their samples under operando conditions.”

Beamline scientists also submit their own projects to use the beamline — or others at SOLEIL or worldwide — depending on the material characterization needed. “We do the same work as any researcher in a laboratory,” she summarizes.

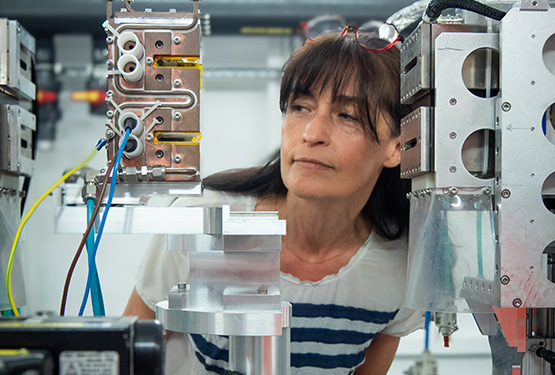

Stéphanie in the experimental hutch of ROCK beamline.

Dedicated support

Her second core mission is ensuring the best possible conditions for external users accessing the ROCK beamline.

Before each visit, Stéphanie helps users identify their needs — beam size, experimental setup, etc. Upon arrival, she fine-tunes the settings and discusses safety aspects with support from the beamline’s technical engineer.

Then the experiment begins.

“I make sure users can operate as autonomously as possible, so they can work day and night in shifts,” she says. “We usually welcome between three to six people depending on the experiment’s complexity and chemical risks.”

But autonomy doesn’t mean being left on their own. Before stepping away, she shows users how to monitor data acquisition overnight.

Meanwhile, she checks the quality of the data: “We often debrief the next morning on what was recorded during the night.”

Stéphanie remains on-site during user experiments, but is also on call — until 11 p.m. on weekdays and 8 p.m. on weekends. “Luckily, we can access our setups remotely,” she says. “So I can support users with just a phone call.”

After the experiment, she and her team assist with data retrieval and analysis.

Teamwork, even in her own research

Stéphanie also regularly conducts her own experiments on the ROCK beamline — rarely alone. After each run, she discusses the results with collaborators and keeps up with scientific literature.

She and her team also work on commissioning [2] new equipment or techniques. “In May, for example, we’ll attempt our first tomography experiment [3] an original idea from Valérie Briois, ROCK’s beamline manager,” says Stéphanie.

Writing publications, submitting project proposals (including for ANR funding), and presenting scientific results are all part of her routine — as is participating in the life of the ROCK team and SOLEIL more broadly.

Add in beamline maintenance and continuous technical upgrades, and it’s a full schedule. “I don’t have one typical day — I have four!” she laughs.

A constant renewal

Her days are full of new faces, learning, and discovery. Stéphanie thrives on this ever-changing rhythm: “We’re lucky to interact with researchers from all disciplines and nationalities,” she says. “No two experiments are alike. Each is enriching, both scientifically and personally.”

She also values the freedom to choose collaborators and join international projects. “Our 29 beamlines welcome new teams every week — sometimes even more often. The topics and people constantly change.”

She adds: “There are few places as vibrant with ideas and energy. And with over sixty different professions at SOLEIL, it’s endlessly fascinating.”

SOLEIL II: a new lease on life for the synchrotron

Twenty years after SOLEIL’s creation, both science and the synchrotron’s role have evolved dramatically. The facility must now adapt to new research frontiers — and that brings new projects for Stéphanie as well. “It’s hard to believe it’s been twenty years. Maybe it’s because I helped design two beamlines — and the last one only opened to users in March 2015, just ten years ago,” she says.

In August 2021, SOLEIL replaced the magnet that produces X-rays for the ROCK beamline with a “superbend” — a new-generation permanent magnet designed in-house.

“SOLEIL needed a new machine to keep science shining bright.”

This new magnet, implemented less than five years ago, increased photon flux on the ROCK beamline and enabled new types of sample characterization. “There’s a constant sense of renewal. Time seems to stand still,” she reflects. “But the machine producing the photons is aging. If not renewed, breakdowns will multiply.” Fourth-generation synchrotrons with smaller, brighter electron sources are now the norm. “SOLEIL needed a new machine to keep science shining bright,” she concludes.

The importance of critical thinking

With her years of experience at the synchrotron, does Stéphanie have any advice for those interested in a similar path?

“The line between chemistry and physics isn’t that clear-cut. Doing synchrotron experiments doesn’t require you to be a physicist,” she says. “Interdisciplinarity is key here — but coding skills are definitely a plus.”

She believes perseverance, rigor, curiosity, and open-mindedness are also essential traits for researchers. “Being critical of yourself and your results is just as important,” she adds.

“If an experiment fails, repeat it. If results look strange, interpret them differently. And with AI soon to be fully integrated into research, we must learn to critique it in order to use it wisely.”

Committed to others

Beyond her role as beamline scientist, Stéphanie has also been active in SOLEIL’s employee representative bodies for the past ten years. “Because of my background, I’m very sensitive to lab safety,” she explains.

She is a member of the Social and Economic Committee (CSE), which represents staff and monitors working conditions. This involvement is close to her heart and, in her view, “a real opportunity”: “It helps me better understand the work of colleagues in completely different roles — people I’d otherwise rarely meet — and deepens my understanding of how our civil society operates.”

Through the committee’s collective efforts, she hopes to improve her colleagues’ daily lives.

Stéphanie is also “obviously” very attuned to women’s rights — globally and in the workplace.

“Throughout my studies, my job, and among those around me, I was spared the discrimination or violence some women face,” she says.

“Naively, I didn’t immediately grasp the reality of being a woman: to me, being born female felt the same as being born male,” she admits. “I never really thought about how the world was shaped by and for men — like doors that don’t open properly for left-handers,” she adds.

While her busy life leaves little room for it now, she hopes to “fully commit to sisterhood” one day.

A healthy mind in a healthy body: Stéphanie during her participation in an edition of the “La Parisienne” race - with SOLEIL logo!

And when she’s not on-site, she devotes her time to her five-year-old son: “He’s at the center of my new interests,” she smiles. “Watching him grow is both fascinating and a bit scary,” she admits. “I’m a bit of a contemplative aesthete, always chasing time to do things while observing them.”

This personality trait also shows in her approach to reading: “I like diving into a book, then taking time to reflect on what I’ve just discovered.”

Whether at work, with others — colleagues, loved ones, or strangers — or during her leisure time, Stéphanie remains guided by curiosity and the joy of discovery.

| Stéphanie wanted to dedicate this portrait. "To my dear mother..." |

Stéphanie Belin's mini biography

1997: PhD in Materials Chemistry, Solid State and Molecular Inorganic Chemistry Lab, Rennes 1 University, France

1997–1998: Postdoc, Institute of Condensed Matter Chemistry of Bordeaux (ICMCB), France

1998–1999: Temporary Teaching and Research Associate (ATER), Institute of Nuclear Physics (IPN), University of Orsay (now Université Paris-Saclay), France

1999–2005: Research Engineer, CNRS, Laboratory for the Use of Electromagnetic Radiation (LURE), Saint-Aubin, France

Since 2005: Beamline Scientist (SAMBA, then ROCK), Synchrotron SOLEIL, Saint-Aubin, France

In Stéphanie's library

Une vie possible, by Line Papin

Du Domaine des murmures, by Carole Martinez

Medusa, by Isabelle Sorente

[1] SOLEIL stands for Source de Optimisée de Lumière d'Énergie Intermédiaire du LURE.

[2] Commissioning is a quality process designed to ensure that systems and equipment function as intended and meet defined requirements.

[3] "Supported by our specialist colleagues, the first tomography tests have proved very encouraging. To be continued!"