When polarized light is directed at a material, it interacts with the material depending on chemical and magnetic properties of the latter. The scattered light creates a diffraction pattern that contains information about both. Traditionally, separating magnetic and chemical signals requires two independent measurements with different polarizations, or using a polarization analyzer, complicating the optical setup. Recently, scientists from SIMaP, Institut Néel, and the ESRF in Grenoble developed a new method at the HERMES beamline that allows separation of magnetic and chemical images from a single microscopy measurement.

Polarized light consists of electromagnetic waves that oscillate in specific directions, while the waves of unpolarized light, such as sunlight, oscillate in all directions. There are several types of polarization: linear, where the waves oscillate in a single plane; circular, where the waves rotate around the direction of propagation; and elliptical, which combines elements of both linear and circular oscillations.

Light interacts with the material's chemical and magnetic properties. If the material responds differently based on the polarization of the light, it is said to exhibit dichroism, a characteristic found in magnetic materials. This property enables the separation of the material’s chemical and magnetic responses by combining two independent measurements taken with different polarizations. Alternatively, a polarization analyzer can be added to the optical setup to analyze these responses.

Magnetic materials are essential in many technological applications, including information storage, computing, and energy generation, making their study and control significant for society. Since magnetic phenomena occur at the nanoscale, visualizing the magnetic structure with nanometric spatial resolution is key for understanding their behavior. This capability is provided by advanced microscopy techniques.

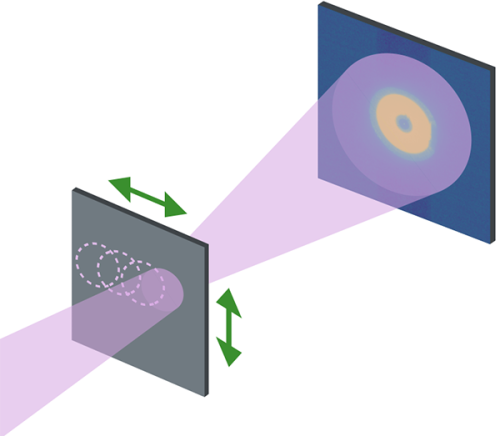

X-rays are particularly well-suited for microscopy since they can penetrate micrometers of material while achieving nanometric resolution. One such technique is ptychography, in which a sample is scanned point by point by the X-ray beam, overlapping the illuminated areas, while an X-ray camera records the scattered X-rays for each scanned position (figure 1).

Figure 1: Ptychographic microscopy uses X-rays to illuminate a material one point at a time, with each illuminated area overlapping the previous one. The transmitted X-rays scatter and are captured by a camera. The collected data is then analyzed to extract the material's chemical and magnetic information.

An interesting advantage of ptychography is that the redundancy of information, given by the overlapping illumination, allows for the recovery of more data than a single image can provide. This includes details such as the shape of the scattered beam, its positions during scanning, and, notably, the ability to disentangle multiple incoherent waves.

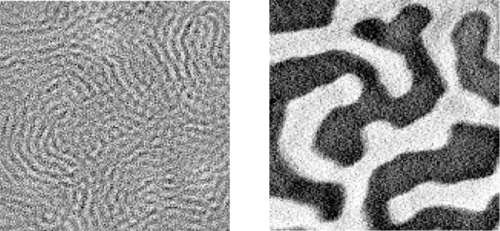

In this study, scientists leveraged the redundancy of information in ptychography to extract both magnetic and chemical signals by treating them as two independent incoherent modes for reconstruction from the diffraction pattern. (figure 2).

Figure 2: Chemical (left) and magnetic (right) images obtained simultaneously from a single ptychography measurement on a Co/Pt multilayer thanks to a multimodal analysis (area of 1 µm2).

The chemical image (uniform grey color, except for the noise) indicates that the concentration of Co in the sample is uniform. In the magnetic image, black and white areas indicate the presence of magnetic domains: the black areas represent magnetization pointing outward from the screen, while the white areas represent magnetization pointing inward the screen. In this maze-like pattern, stripes are approximately 100 nm wide.

The experimental dataset demonstrating this new method was obtained at the HERMES beamline, which specializes in high spatial resolution ptychography. The multimodal reconstruction was implemented using the PyNX library, which facilitates image reconstruction from coherent diffraction imaging techniques, including ptychography. To demonstrate this new approach, single linear polarization scans were conducted, and the validity of the method was confirmed by comparing the results to the typical contrast obtained from measurements using both positive and negative circular polarizations, yielding matching results.

Overall, the capability of multimodal ptychography to resolve orthogonal polarizations in a single measurement, without requiring a physical polarization analyzer, is of great interest for magnetic imaging. This method is particularly promising for imaging more elusive or complex magnetic configurations, such as antiferromagnets, and could also be applied in wide-angle scattering geometries where the choice of incident polarization do not allow easily disentangling chemical and magnetic information.